Oct 25,2024

Analysis: Despite being associated with the supernatural, Irish people traditionally saw Hallowe'en as a night for fun and games

The ancient Irish marked the eve of the beginning of Samhain, the season of winter, and one of the four major pre-Christian festivals. The festivities of Oíche Shamhna began at sundown on October 31st and also heralded the end of one pastoral year and the beginning of another. What became known as Hallowe'en is not an Irish invention – it was celebrated in other parts of Europe - but many Irish rituals and traditions were adapted by others.

This old, so called 'Celtic’ calendar was followed in parallel to the conventional Gregorian calendar by our recent ancestors. The former was intrinsically linked to agricultural events, and reflected how rural people were aware of the cycles of nature and deeply connected to land for survival. In the old calendar too, certain times of year were deemed appropriate for particular rituals. Marking the time between seasons, Hallowe'en was a night on which the supernatural was deemed to be at its most active and powerful.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Despite being associated with the scary supernatural, Irish people traditionally saw Hallowe'en as a night of fun and games. I have written elsewhere about the customs and rituals that endured until the mid-20th century, from the ritual traditions to predictions and spells. Many Irish traditions involved seasonal foodstuffs or reusing materials they already had, seldom would people go out and buy items for Hallowe'en.

In terms of dressing up, people disguised themselves by swapping clothing with others, rubbing their faces with soot, using false names and changing their voices before calling to the doors of neighbours looking for contributions of food for their Hallowe'en party. Hallowe'en bonfires were lit to protect from evil forces, but also for people to gather round for merriment and relatively harmless mischief was tolerated on this night.

When safe back at home, there was focus on food, the glut from the harvest allowing a feast of plenty. In Ireland, food was seldom in abundance and sugar was uncommon, so people delighted in sweet apples and hazelnuts, colcannon with butter, fruit brack and people played games with foodstuffs, too.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Hallowe’en was time specific and there was deep significance to the time between sundown on October 31st and dawn the next day. That time too was believed to be a good night of the year for forecasting the weather, along with amateur fortune telling and romantic divination. The latter remains in the modern barm brack, still sold in the shops today, which comes with a novelty ring meaning whoever gets that slice will be the next to wed.

On Hallowe’en night, the souls of ones’ ancestors were believed to return to the family home. Before going to bed that night, chairs were arranged around the hearth to symbolically welcome back the spirits of departed loved ones. It’s a custom that even today may bring comfort to those grieving the loss of a loved one.

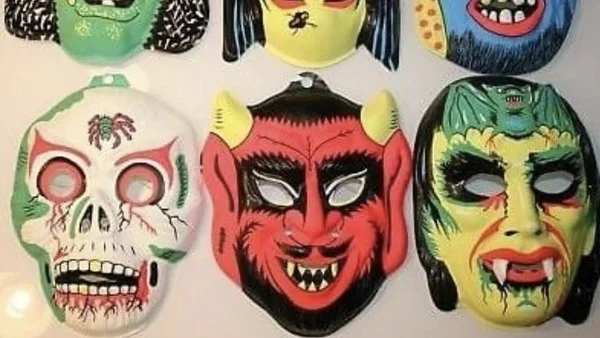

In the 1980s when I was growing up, there was not much deviation from these customs. Shop-bought plastic masks began to appear. There was a limited selection to choose from, and these tended to be saved and reused, with repairs to the elastic when required. Continuing the tradition of the Hallowe’en 'guisers’, costumes tended to be homemade, using anything lying around the house. An ingenious, now rather iconic, costume was the black plastic rubbish bag with holes cut in for head and arms and completed with a belt. It made for an excellent witch or ghoul.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

While available, store-bought costumes were uncommon, and the resultant lack of peer pressure meant parents faced minimal pressure to purchase them. They simply ensured that the pot of sweets at the door (containing mostly chewy sweets and the occasional bar of chocolate) remained topped up for callers.

This is in sharp contrast to today. Hallowe’en is not confined to a single significant night of the year as per the old Celtic tradition. Today, Hallowe’en products begin appearing in shops as early as August, and fireworks can be heard in September.

Hallowe’en dressing up day at primary school has now become a new tradition, an annual feature of the last day before the October mid-term break. Homemade costumes from materials around the home are no longer the norm. Instead, pre-made costumes are available in shops of specific archetypes and characters, a pack can include a mask and accessories. A growing child will require a different costume each year.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

While rooted in ancient traditions, the modern Irish Hallowe'en has incorporated elements from other cultures. In a marked contrast to our relatively impoverished past, Irish wallets expanded in recent decades, and there came to be more consumer choice and availability of products. Plastic indoor decorations such as fake cobwebs and battery-operated ghouls have become commonplace.

Other elements representative of American fashions, such as plastic 'Fall' door wreaths and outdoor ornaments and lighting, have become popular. The pumpkin now holds sway due to its size, wide availability and ease of carving when compared to the traditional turnip, which can be more terrifying with connotations of death, decay and folk horror, with potentially less food waste.

Despite most fireworks being supposedly banned in Ireland, their widespread use suggests otherwise and they have become more popular in recent years at Hallowe’en. One might link them in Irish tradition to outdoor bonfires, but their connection to Guy Fawkes Night in England is more apparent.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Trying to fully preserve the past or mourning lost rituals is futile. Traditions are dynamic and evolve with each generation. However, there continues to be a proliferation of material waste associated with Hallowe’en today in an era of sustainability and environmental concerns. Products such as decorations are in thrall to annual trends. We see how Christmas, and other seasonal celebrations now have new specific themes and looks on an annual basis, preordained by the design industry.

Hallowe'en is no exception. You may have a box of carefully preserved decorations ready to reuse each year, but there will always be new tempting styles or gimmicks. The low price of these items, along with key supermarket product placement, persuades many to pop them into their trolleys along with their weekly shop.

What happens to the costumes and decorations when the children outgrow them? And what happens to the wreath when it fades or goes out of fashion? How easily are these products reused, upcycled or recycled? And why are we buying such things – is it novelty, following trends, consumer culture, or are we looking for a way to satiate our intrinsic need for ritual and tradition? If so, why not look to the long-established traditions we already have? Ask any Gen Xer and they may tell you a 1980s Hallowe’en was not a hardship by any means, and was far friendlier on the environment.

.svg)