Dec 19,2024

Textiles have a powerful role in capturing the history others might prefer to be forgotten. The use of fabric to document and create queer or feminist history and culture is a fascinating way to explore how we tell personal stories without words.

Fabric can be used in so many ways, according to artist Andrea Geyer who weaves queer images into textiles.

She says: "It can be shelter, it can be clothing, it can be a flag, it can be a curtain, it can be a backdrop". It also provides a platform of visibility for those who may be closeted or invisible in society in spoken word or media representation.

In 1930s Britain, Ernest Thesiger laid the groundwork for queering embroidery. Using it as a pastime to recover from being injured, Thesiger’s work proved to be more than just a rehabilitation tool. It was common for WWI veterans to use embroidery to help them with injuries sustained in war, despite this previously being seen as an activity for women only.

As the war became more of a distant memory, the use of embroidery began to be firmly re-established as a ‘feminine’ activity, with fierce gatekeeping from the media in order to keep the binaries of masculine and feminine as distinct as possible.

Viewed in this light, men using embroidery were seen as a threat: ‘Men are beginning to invade territory once thought sacred to her, and in knitting, crocheting, and many other forms of needlework Jack is almost as good as Jill’, read The Courier and Advertiser, on 6 March, 1933.

Not holding back, The Yorkshire Post proclaimed "Shall we regard this as a sign of degeneracy in our male stock?". They argued that men who engaged in needlecraft were effeminate and should have only practiced embroidery in cases where no women were around to do it for them, such as being stuck on a ship or in a ‘jungle camp’.

Symbolism runs deep when it comes to queer identity and fabric. The thread as a single entity is powerful - it does not have to conform to prescribed norms. It has the potential to become so many things; from being part of a woven fabric depicting a neutral landscape, a piece in protest art, made into a pride flag, or sold to raise funds for community projects.

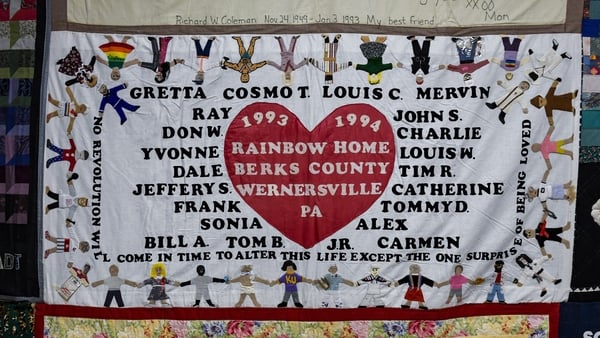

Like queer people, there is no need to conform to what ‘should’ be. Given the horror attached to queer blood during the initial HIV/AIDS wave in the 1980s, pricking a finger making an AIDS memorial quilt makes embroidery even more symbolic.

Threads and the act of weaving them together are also symbolic of the person crafting their own individual identity, sexuality, and community. Each thread is integral to the overall picture, but contributes its own individual colour and texture.

And it's not just fabric: glitter - an integral part of so many rave looks, Pride outfits and queer expression in general - is popular for a reason among the community.

Glitter symbolises the power of solidarity; people may feel fragmented and powerless on their own, but they can be bold and bright when united. There is power in visibility, and a single thread becomes stronger when united with other threads. Glitter is a persistent tool for community building, visibility, and resistance to control and being subjected to sexual and gender norms.

For a lot of LGBTQIA+ people, family is chosen. Elder queer people may not exist in some areas due to being forced to stay in the closet, rejection from biological families, or dying from the AIDS crisis in the 1980s onwards. Glitter is thus a connector to chosen family, a shining beacon to signal to people that it is ok to be bold and bright, and queer people are not going to disappear.

You may have heard of 'glitter bombing', usually used to protest against politicians trying to pass homophobia laws. They are a reminder that no matter your attempts to silence and oppress queer people, you cannot, and like the glitter, they will not go away or have their light dulled by those seeking to oppress.

In Mexico, glitter has also been used to protest alleged police violence. In 2019, women threw pink glitter on a Chief police officer as a protest of the alleged gang rape of a 17 year old girl by four serving police officers.

In 2017, glitter was also used to rebel against religious decrees that queer people are not welcome in the Christian religion. 'Glitter Ash Wednesday' sees glitter used instead of ashes to signify that queer people are welcome, and glitter blessings can be given by anyone at any time to welcome queer people of faith. They have given blessings to over 35k people so far and can even send you glitter to do your own.

Fabric can be an incredible tool for creating visual language. We have seen fabric being used to protest against abortion laws, as seen with activist group Speaking of Imelda and their use of giant red knickers in 2018.

That same year, a rape trial in Ireland saw a defence lawyer refer to the type of underwear a 17-year-old was wearing, informing the jury that: ‘You have to look at the way she was dressed. She was wearing a thong with a lace front’. The 27-year-old defendant was found not guilty, and protests across Ireland ensued with many protestors holding up lace underwear and chanting ‘this is not consent’.

Social media was also utilised by people outraged at the verdict as they shared photos of underwear under the hashtag #thisisnotconsent, and this method of digital activism combined with well attended protests across the country. For a country that historically did not talk about sexual violence, this was a seismic shift in how victim blaming was perceived and challenged.

Fabric can be an artform that builds community and changes cultures. There are many tools for a revolution; a sewing box or tub of glitter is part of this toolkit.

If you have been affected by issues raised in this story, please visit: www.rte.ie/helplines.

.svg)